INTERNATIONAL EXAMPLES

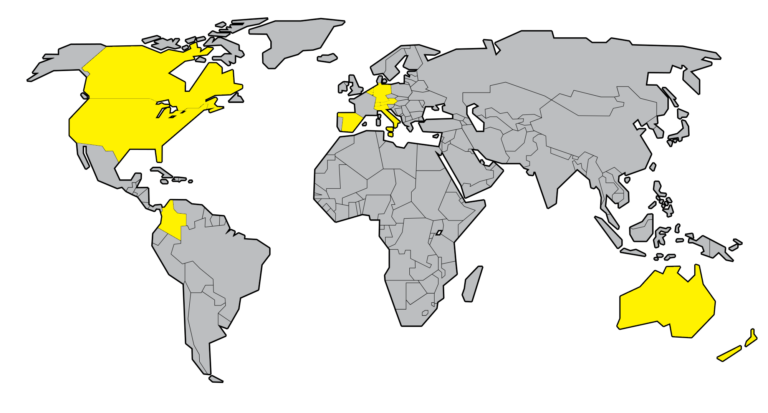

There are predominantly two models of assisted dying around the world. The first, most notably found in all the states in Australia, New Zealand, Oregon and 9 other states in the United States of America, only provides assistance to those who have six or fewer months (12 months for neurodegenerative diseases such as Motor Neuron Disease in Victoria) left to live; whereas the broader model, found in most other jurisdictions, enables a choice for both those who are terminally ill and those who are intolerably suffering.

The broad form of assisted dying is legal for people in Austria, Belgium, Canada, Columbia, Italy, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Portugal, Switzerland, and Spain.

Assisted dying is also legal or soon to become legal for the terminally ill only in Germany, the Isle of Man & Jersey. Legislation is also being debated in the UK parliament, covering England & Wales, and the Scottish parliament.

The House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee produced an extensive report into Assisted Dying in February 2024 with details of all the international examples.

On 1 January 2022 the Statute on the Will to Die, which regulates assisted dying in Austria, came into force.

This followed after Austria’s highest court struck down a ban on assisted dying in 2020, and ordered the Government to introduce legislation to clarify the law in 2021. The case was brought by several citizens, including a doctor and a 56-year-old man who suffers from multiple sclerosis and is unable to end his life without someone else’s assistance. Austria’s constitutional court held that prohibiting assisted dying unjustly violated an individual’s right to self-determination, as the law ensures people are able to exercise the right to shape their own life as well as the right to a dignified death.

ELIGIBILITY

In Austria, a valid patient’s dying will allows individuals to obtain a lethal preparation from a pharmacy and self-administer it. In order to qualify a person must meet strict legal conditions, including among others that:

- They are at least 18 years old.

- They have a severe, incurable illness affecting their entire life.

- There must be no doubt that the person is capable of making a decision.

SAFEGUARDS

In addition to stringent eligibility criteria, Austria’s law also includes a series of robust safeguards including:

- Two physicians, one with a palliative care (PC) diploma or specialisation, are required to approve the application.

- A notary, lawyer or patient advocate draws up a dying will.

- The patient’s capacity to make a decision must be confirmed, and mental health assessment by a psychiatrist or psychologist is required if impairment is suspected.

- A waiting period of 12 weeks is mandated. For those in the terminal phase of an illness, this period is reduced to 2 weeks.

Assisted dying is currently permitted in all 6 Australian States. Victoria was the first state to pass legislation which came into force in 2019. Similar legislation came into force in Western Australia (2021), Tasmania (2022), New South Wales, South Australia & Queensland (2023). Voluntary assisted dying (VAD) will be available in the Australian Capital Territory from 3 November 2025 and the Northern Territory has published a report recommending legislation in line with the other Australian states.

VICTORIA

The latest report from Victoria (2023/24) shows that Voluntary assisted dying deaths represented 0.84% of all deaths in Victoria. 554 applicants who were issued with a permit subsequently died. Of these, 180 deaths (32%) were from unrelated causes.

ELIGIBILITY

In Victoria, a doctor can only prescribe life-ending medication if they meet multiple qualifying conditions. These include that:

- They are aged at least 18 years old and have decision-making capacity

- They have made three clear and separate requests for assistance and done so without evidence of any coercion; these requests must be both verbally and in writing

- They must have an advanced disease that will cause their death and that is:

- likely to cause their death within six months (or within 12 months for neurodegenerative diseases like motor neurone disease)

- causing the person suffering that is unacceptable to them.

The law also explicitly prohibits providing assistance to die simply because of a mental illness or disability.

SAFEGUARDS

In addition to stringent eligibility criteria, Victoria’s law also requires that:

- Two doctors (who have undertaken mandatory training before they are able to conduct eligibility assessments) must verify that someone meets the eligibility criteria and assess that no-one is forcing or influencing the person to request it.

- There must be a 10 day cooling off period between someone requesting and having an assisted death

- Doctors who do not want to be involved in the process of assisted dying are able conscientiously to object

- Medical practitioners must also remind the person they do not have to go ahead if they change their mind at any time throughout the process.

- An independent oversight board must monitor the application of the law and report to the Victorian parliament on its progress

In Victoria, assisted dying is permitted either in the sense of someone self-administering medication, or if someone is physically incapable of ending their life a doctor can also directly administer the medication.

Since 2002, assisted dying has been formally allowed for both the incurably suffering and terminally ill in the Netherlands and Belgium; later also becoming legalised in Luxembourg in 2009. Previously, doctors in the Netherlands also had a criminal defence for assisted dying in very restricted circumstances.

Though not identical, the law on assisted dying in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg is substantially similar and multiple comprehensive and independent studies have found no evidence of it failing to protect vulnerable people. Indeed, an influential report on the Netherlands concluded that ‘there is no current evidence for the claim that legalised PAS (assisted dying) or euthanasia will have a disproportionate impact on patients in vulnerable groups’.

ELIGIBILITY

Broadly, assistance can be provided either by someone taking life-ending medication themselves, or by a medical practitioner administering the substances. In order to qualify for assistance a person must typically:

- Be aged at least 18 years or older

- Suffer unbearably with no prospect of improvement, from either a terminal, chronic, or psychiatric illness

- Have made a voluntary and ‘well considered’ request

- Have requested assistance to die after concluding that there is no reasonable alternative.

Theoretically, it is also possible for those aged under 18 to have an assisted death in the Benelux countries, but in reality such instances rarely occur and are subjected to more exhaustive safeguards. For example, between 2004 and 2017 only 7 cases occurred in Belgium. Beyond this, it is also possible to provide assistance to someone unable to communicate their wish at the moment of death under the Benelux model, if they had previously stated this was their wish in writing when they had mental capacity.

SAFEGUARDS

In order to qualify for an assisted death a series of ‘due care’ requirements also exist, such as:

- A doctor must confirm that someone is eligible for an assisted death; this means that they must inform a patient of their condition and any reasonable alternatives

- A second independent doctor must then also confirm in writing someone’s eligibility

- Each instance of assistance must then be reported to an independent review committee, who will investigate the doctor’s decisions and refer the case for criminal prosecution if necessary. (However, no doctor has ever been prosecuted.)

Typically, a right-to-die is also recognised alongside a right of access to palliative care in the Benelux countries. For example, over 70% of people who request an assisted death in the Flanders Region of Belgium will have exhausted the options of palliative care beforehand.

It has been legal for adults of sound mind with intolerable and irreversible suffering to have an assisted death in Canada since 2016. In 2023 4.7% of deaths in Canada were as a result of medical assistance and 95.9.% of those are where their death is otherwise “reasonably foreseeable”. There is no evidence that the law has been abused or has harmed vulnerable people. In fact one study has found the exact opposite, as traditionally vulnerable demographics are less likely, than other groups, to have an assisted death under Canada’s law.

ELIGIBILITY

In Canada, assistance can be provided either by someone taking life-ending medication themselves, or by a medical practitioner implementing a person’s wish. However, in order to qualify a person must meet strict legal conditions, including among others that:

- They are at least 18 years old and mentally competent

- They have a grievous and irremediable medical condition specifically:

- have a serious illness, disease or disability;

- be in an advanced state of decline that cannot be reversed; and

- experience unbearable physical or mental suffering from the illness, disease, disability or state of decline that cannot be relieved under conditions that the person considers acceptable

- They have made a voluntary decision and given ‘informed consent’.

Importantly, someone ‘does not need to have a fatal or terminal condition to be eligible for medical assistance in dying’ in Canada.

Until March 17 2027, pending a review, the law also bans helping people who seek an assisted death solely on the basis of psychiatric suffering.

SAFEGUARDS

In addition to stringent eligibility criteria, Canada’s law also includes a series of robust safeguards including:

- Someone can only raise the prospect of an assisted death themselves i.e. a doctor cannot prompt the topic first

- A medical professional must confirm that someone is eligible for an assisted death, and a second such professional must also agree

- A request must be in writing and signed by an independent witness

- All cases must be reported to an independent monitoring board.

In the case of people suffering from intolerable but non-life threatening illnesses, the law also imposes additional safeguards such as:

- Mandating that people are directed and offered professional services to ease their suffering e.g. professional counselling, disability support, and palliative care

- Requiring at least a 90 day assessment period to ensure someone is eligible and wants an assisted death.

Intentionally ending another person’s life to relieve them of suffering has been decriminalised in Colombia since 1997. In 2015, this practice was subjected to a set of strict nationwide regulations, which limited assisted dying (in the sense of administering life-ending medication) to adults who are terminally ill. According to the Ministry of Health in Colombia, 52 people have received an assisted death following the health directive issued in 2015.

Importantly, Colombia’s governing guidelines do not define a ‘terminal illness’ by reference to a specific progress, but instead as ‘anyone who carries a serious illness or pathological condition that has been diagnosed accurately by a physician, showing a character progressive and irreversible, with fatal prognosis near or in relatively short time, which is not susceptible to a curative treatment and proven, that would modify the prognosis of imminent death…’.

ELIGIBILITY

In order to qualify for an assisted death in Colombia, someone must:

- Be at least 18 years old

- Freely and unequivocally request an assisted death

- Suffer from a terminal illness and have had all alternative treatment options, but especially palliative care, presented to them.

Notably, someone can either state their wish for assisted death when they have a terminal illness, or do so earlier in anticipation of a terminal illness through an advanced directive. However, assistance cannot be provided until someone becomes terminally ill. Theoretically, it has also been possible for someone under the age of 18 to request an assisted death in Colombia since 2018, but there are no known cases of this happening.

SAFEGUARDS

- Independently of a right-to-die, everyone has a guaranteed right to palliative care

- A physician must present the request for an assisted death to a committee of experts, including a medical expert, lawyer, and mental health expert, who must then approve or decline the request within 10 days

- If approval is given by an oversight committee then there must be a 15-day waiting period before assistance is provided.

In 2019, Germany’s highest court clarified the law on assisted dying and overturned legislation that had previously banned it. As a result, assisted dying is now legal for both those who are either terminally ill or intolerably suffering in Germany. However, this ruling does not mean that there is a law regulating assisted dying or specifying who is eligible, the manner by which a person can be assisted, or appropriate safeguards for assisted dying in Germany – it remains for Germany’s Parliament to set out that detail.

Germany’s 2019 judgement built upon an earlier court ruling from 2017, where Germany’s highest court also held that in exceptional cases someone that is ‘seriously and incurably ill’ cannot be denied access to life-ending prescriptions, provided they ‘can freely express their will and act accordingly’.

It is known that between 2017 and July 2019, 127 people submitted an application for life-ending medication in Germany, and that at least 20 people were prescribed dosages.

In 2019, Italy’s highest court confirmed that it is not illegal, under certain circumstances, to help someone intolerably suffering to end their life.

However, unlike other countries, this means that Italy does not have a formal law setting out who is eligible, the manner by which they can be helped, or additional safeguards for assisted dying. Instead, the nature of the court’s decision means someone can only assist another with confidence, if someone’s personal circumstances closely mirror the facts upon which Italy’s court made its judgment.

ELIGIBILITY

For someone to be confident that they are not breaking the law by assisting another to end their life, the person they are assisting should:

- Have made an autonomous and freely informed decision

- Have an illness or condition that is irreversible

- Have a condition which causes physical or psychological suffering, which they find intolerable

- Be kept alive by means of life support treatments i.e. artificial nutrition or respiration

- Be fully capable of making free and conscious decisions.

Importantly, although this means that assisted dying is only permitted in narrow circumstances for Italy, there is no restriction to help those only with a certain life-span e.g 6 or fewer months left to live.

New Zealand voted to legalise assisted dying as part of a nationwide referendum in 2020, and legislation came into effect in late 2021. 65.1% of New Zealand voters backed proposals that allows doctors to help adults who are terminally ill end their life, provided that they are of sound mind and have a settled and uncoerced wish.

The latest annual report said that 344 people had an assisted death in 2023/24 (0.8% of all deaths).

ELIGIBILITY

Under New Zealand’s legislation, a doctor can only prescribe someone life-ending medication if certain stringent conditions are met. These include that the individual:

- Is at least 18 years old and able to make an informed decision

- A citizen or permanent resident of New Zealand

- Is suffering from a terminal illness that is likely to result in death within six months

- Is experiencing unbearable suffering that cannot be relieved in a manner that the person considers tolerable

The law specifically prevents someone from qualifying for assistance on the basis of advanced age, a mental health concern, or solely due to a disability.

SAFEGUARDS

In addition to stringent eligibility criteria, New Zealand’s forthcoming law has multiple safeguards, including:

- Two doctors must verify that someone meets the eligibility criteria, and satisfy themselves that someone has made their wish free from pressure from any other person

- In the event of any concern about an individual’s capacity, a mental health specialist should undertake an assessment

- Someone must put their wishes in writing; this request must be signed and dated

- Doctors who do not want to be involved in the process of assisted dying must be able to object conscientiously

- After assistance has been administered, it must be reported to an independent oversight body.

New Zealand’s legislation also enables someone to digest the life-ending medication, or for a doctor or nurse to inject a lethal dose of medication.

Assisted dying has been legal in the US state of Oregon for adults of sound mind who are terminally ill since 1997. Based on Oregon’s legislation, assisted dying has also become legal for the terminally ill in Washington, Maine, New Jersey, New Mexico, Washington DC, Vermont, California, Colorado, and Hawaii. In Montana, a separate court case decriminalised assisted dying for adults of sound mind who are terminally ill.

As with assisted dying legislation elsewhere, medical assistance accounts for a tiny percentage (less than 0.5%) of all deaths in Oregon, and nearly a third of all people who apply for assistance do not end their lives.

ELIGIBILITY

In Oregon, a doctor can only prescribe people with life-ending medication if they meet clear qualifying criteria. If eligible, someone must then choose to take a life-ending substance themselves i.e. without assistance from others. In order to qualify someone must be:

- At least 18 years old and ‘capable’ (mentally competent)

- Suffering from a terminal illness which means they are likely to die within 6 months

- Have requested assistance on 3 separate occasions; both verbally and in writing.

Importantly, this means that someone who endures unbearable suffering or pain, but is not terminally ill, is not eligible for assistance to die under Oregon’s model.

SAFEGUARDS

In addition to stringent eligibility criteria, Oregon’s law also requires that:

- A doctor must confirm that someone has a terminal condition, is making a voluntary request, and understands the full implications of that decision i.e. they are aware of alternative treatments and potential risks

- A second independent doctor must then confirm again that a person has a terminal diagnosis and has made a voluntary and informed decision

- If there is any suspicion that someone’s mental health could be affecting their judgement, they must be referred for counselling and deemed not to have impaired judgement

- There must be at least a 15 day cooling off period between someone’s second and third request.

Spain’s parliament approved an assisted dying law for people with terminal and intolerable illnesses which came into force in June 2021.

ELIGIBILITY

Assistance can be provided either by someone taking life-ending medication themselves, or by a medical practitioner administering the fatal substances. In order to qualify for assistance someone must be:

- A Spanish resident

- An adult, who is ‘fully aware and conscious’ at the time of requesting assistance

- Suffering from a serious and incurable disease, or from a serious, chronic, and incapacitating condition causing intolerable suffering.

Under Spain’s law it is also possible for someone to state in advance their desire for an assisted death, and for this document to take effect in the event that they later lose mental capacity.

SAFEGUARDS

In order to ensure that someone is making a voluntary and uncoerced decision, stringent safeguards must also be satisfied, including:

- A requirement for patients to request their death on four separate occasions; the first two requests must be in writing and submitted more than two weeks apart

- A requirement for someone to be informed of all alternative medical options, including palliative care

- Two independent doctors must confirm that someone meets the eligibility criteria for an assisted death within 19 days of receiving the second written request

- A regional commission, including medical, legal, and nursing experts must approve the request.

Spain’s law also enables medical staff with an ideological or religious objective to remove themselves from the process.

Unlike other countries, Switzerland does not have formal legislation governing assisted dying. Instead, legal cases have broadly set out the basis for providing an assisted death in Switzerland, and non-profit organisations which provide assistance have created their own set of internal safeguards.

ELIGIBILITY

Broadly speaking, Articles 114 and 115 of the Swiss penal code have been interpreted to mean that assisted deaths can only be provided to those who are:

- Mentally competent and who have given considerable consideration to their wish

- Are physically capable of ending their lives themselves

- Have constant and unbearable (physical or mental) suffering with no prospect of improvement

- Have been confirmed by a physician, as having no reasonable alternative to reduce their suffering.

Notably, this means that Switzerland does not limit the option of an assisted death only to Swiss residents. Hence it is estimated that more than one person a week travels from the UK to Switzerland for an assisted death.

SAFEGUARDS

The main limitation under Swiss law is that assisted dying must be provided for ‘non-selfish’ reasons. This means that assisted dying is normally provided by non-profit organisations. There are four Swiss main organisations which offer assistance to UK citizens: Lifecircle, EX International, Pegasos, and Dignitas. According to Dignitas’ procedures, someone can only be assisted to die if:

- They cannot be directed to appropriate alternative counselling e.g. pain management experts or palliative care referrals

- They have made a written formal request for assistance

- Up to date medical documentation has been supplied which demonstrates a person’s suffering

- An independent doctor has confirmed that they are willing to prescribe life-ending medication, and then has two consultations with the individual in question to confirm their willingness again

- Sufficient documentation has been provided to enable Dignitas formally to register the death with the Swiss authorities

- An in-depth interview has occurred and an official from Dignitas is confident that the individual has mental capacity and is not being coerced or pressured into ending their life.

Further information on safeguards can be found on the other organisations’ respective websites.