Last week, the committee overseeing the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill held crucial evidence sessions, hearing from experts, medical professionals, and those with lived experience. The evidence sessions provided powerful insights reinforcing the urgent need for a compassionate, safeguarded assisted dying law.

We attended the evidence sessions at Parliament. Here are our five key takeaways from the sessions.

- Compassion Must Be at the Heart of This Bill

The committee invited loved ones and family members of individuals directly impacted by the current law to share their stories.

A profoundly moving testimony from Pat Malone highlighted the unbearable suffering faced by dying people. Pat’s sister had motor neurone disease and travelled to Dignitas to avoid the slow and harrowing decline she knew she would face in the UK. Although relieved to get the death she deserved, Pat will never accept that she had to travel “1,000 miles from home” to do it.

“She should have died in her house with her family and her dogs on the bed. She should not have been denied that.”

We also heard from Liz, whose brother chose to have an assisted death in Australia. Liz’s brother had terminal cancer and wanted to take control of the timing and place of his death.

“We were all there: my mum, my dad, me, his wife. We sat there and held his hand—and what a gift.”

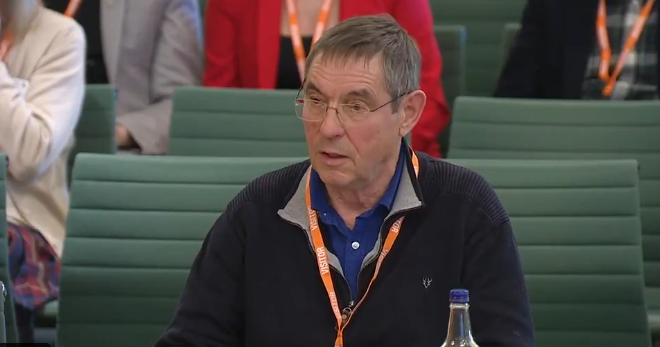

The personal testimony moved many on the committee to tears, and we highly recommend watching it back if you can. Watch from 15:00 PM for the family testimonials.

2. Coercion Concerns Are Unfounded

Evidence from Australia and the U.S., where assisted dying laws are in place, made it clear: coercion simply doesn’t happen. Safeguards ensure decisions are made freely, and in practice, many patients face more pressure to continue treatment than to end their lives.

It was very reassuring to hear from the American and Australian doctors who work extensively on assisted dying that they have no concerns over coercion.

Dr Ryan Spielvogal, Senior Medical Director for Aid in Dying Services at Sutter Health, USA, said: “I’ll tell you in practice, it just doesn’t happen. I have helped many people through this process in many states, and I have never seen a case of even suspected coercion. People just aren’t that good at acting.”

3. Doctors Should Not Be Gagged

Medical professionals shared concerns about the current restrictions on discussing assisted dying with patients. In countries with legal frameworks, open conversations improve end-of-life care, giving patients all available options rather than forcing them to seek information elsewhere and make lonely decisions.

When asked about a potential ‘gag clause’ that would prevent doctors from talking about assisted dying to patients, Dr Mulholland, Honorary Secretary at Royal College of General Practitioners, said: “We are very protective of our relationship as GPs, and want to give patients the options that they might want to choose for themselves. We are not pushing anyone to make any decisions, but supporting them through their end-of-life journey. We would want to protect that in whatever way, so we feel that a service we can signpost to would be the most appropriate as the next step.”

4. Eligibility Should Be Altered

Experts testified that the six-month prognosis requirement is too rigid. Many terminal illnesses do not follow a predictable timeline, and eligibility should focus on intolerable suffering rather than an arbitrary timeframe.

Dr Cam McLaren, a Medical Oncologist from southeast Melbourne, recommended to MPs that they “increase the eligibility criteria for an assisted death from six months to twelve” and remove unnecessary waiting periods.

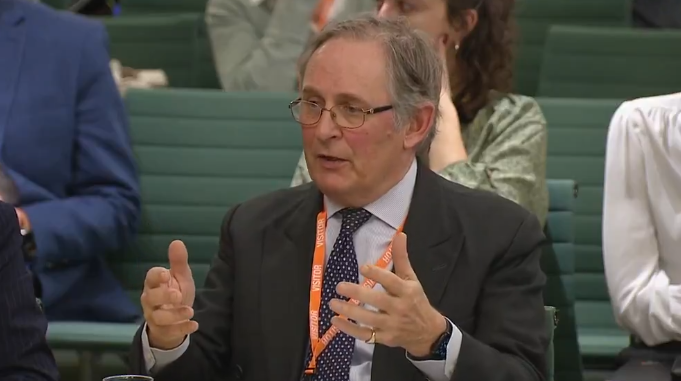

Sir Nicholas Mostyn said that an arbitrary 6-month prognosis will unfairly discriminate against those with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s: “I do believe very strongly—and this is not an expansion but a more appropriate focus or redefinition of terminal illness—that it should be focused on suffering.”

5. The High Court Requirement Is Unnecessary

Several legal experts expressed doubts about the need for High Court approval. Existing models in other countries show that robust safeguards can be upheld without adding unnecessary legal hurdles that could delay access to assisted dying for those in need.

Claire Williams, Head of Pharmacovigilance and Regulatory Services, advocated for the Bill to move away from a High Court judge, instead having a multidisciplinary panel. “It is having that collective view, ensuring that everybody is happy and that it is exactly what the patient wants. I believe it should be a committee/panel-based approach for the final decision.”

We welcome any efforts to remove unnecessary barriers to compassion for individuals at the end of their lives.

For further comment or information, media should contact Nathan Stilwell at nathan.stilwell@mydeath-mydecision.org.uk or phone 07456200033.

Media can use the following press images and videos, as long as they are attributed to “My Death, My Decision”.

My Death, My Decision is a grassroots campaign group that wants the law in England and Wales to allow mentally competent adults who are terminally ill or intolerably suffering from an incurable condition the option of a legal, safe, and compassionate assisted death. With the support of over 3,000 members and supporters, we advocate for an evidence-based law that would balance individual choice alongside robust safeguards and finally give the people of England and Wales choice at the end of their lives.